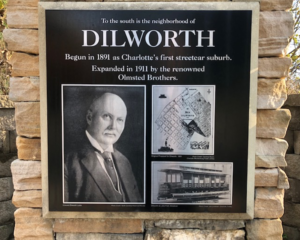

As soon as famed inventor Thomas Alva Edison electrified Charlotte’s streetcar system in 1891, developer Edward Dilworth Latta transformed former farmland into Dilworth, first of the city’s ring of “streetcar suburbs.”

In 1911 Latta expanded beyond the original grid of straight streets. He hired the renowned Olmsted landscape firm from Boston to add winding Dilworth Road and curving sidestreets.

The neighborhood eventually lost its luster to newer suburbs — until young people began moving in and renovating the big old houses during the 1960s – 70s. Today it is once again one of Charlotte’s most desirable areas.

What’s to see and do? We’ll start at Latta Park in the heart of the Olmsted section and walk a loop that ends on straight Kingston Avenue in the 1891 section. Look for red-brick Georgian Colonials, wood shingled Bungalows, the Moderne-style Myrtle Apartments, and some eye-popping religious architecture, all nestled under a canopy of century-old oaks.

How long? Roughly 2 miles. If you are a brisk walker, that’s about 1 hour. If you stroll, amble or dawdle (all are much encouraged), it’ll take longer.

Please stay on the public sidewalk. None of these places are open to visitors.

Where to start? Arriving by car, you’ll find a few parking spots on the edge of Latta Park’s soccer field, across Dilworth Road from the yellow sculpture made out of streetcar rails (roughly 1601 Dilworth Road East).

STREETCAR RAIL SCULTURE – 1600 Dilworth Road East

To create Time Line, sculptor Robert Winkler of Asheville used actual streetcar rails salvaged when Dilworth streets were being repaved. Charlotte’s first streetcar ran out to Dilworth in May of 1891. The last ran in March of 1935. One route followed South Boulevard and East Boulevard. Another line ran here along Dilworth Road.

Dilworth filmmaker Donald Devet made a delightful half-hour video about Time Line and Dilworth history.

As you face the sculpture’s explanatory panel, turn right. Walk in-bound on Dilworth Road, crossing the park and crossing Romany Road. Then continue up the hill on Dilworth Road.

FRANK O. SHERRILL HOUSE – 1401 Dilworth Road

If you grew up in the Southeast in the second half of the 20th century, likely you have fond memories of S & W Cafeterias. Frank Sherrill and a buddy named Fred Weber met as mess sergeants in WWI. They opened their first cafeteria on West Trade Street in downtown Charlotte in 1920 and went on to plant branches from Atlanta to Washington D.C. In an era when the South had few restaurants, Sherrill’s eateries made him wealthy enough to construct this distinguished red-brick Georgian Colonial mansion in 1928.

RANDOLPH SCOTT FAMILY’S HOUSE – 1301 Dilworth Road

George Scott, a prosperous accountant, moved his family out from 4th Ward to suburban Dilworth in 1928. Distinguished local architect Louis Asbury designed the 10-room residence. College-age son Randolph lived here briefly before heading west to Hollywood, where he quickly made many friends, including Cecil B. DeMille and Cary Grant. Randolph Scott starred in over 100 movies, often playing a handsome cowboy. There was even a 1974 hit song “Whatever happened to Randolph Scott?”

The Scott House is an official Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Landmark.

As you continue along Dilworth Road, the walkway into the courtyard of Covenant Presbyterian will be on your right. Duck in, if you like, then come back out and continue down Dilworth Road.

COVENANT PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH – 1000 E. Morehead Street

Cram & Ferguson, nationally esteemed architects based in Boston, provided the Gothic Revival design in association with J.N. Pease Associates of Charlotte. Accents carved in Indiana limestone enliven the rose-tinged North Carolina granite walls. The sanctuary’s cornerstone was laid on April 27, 1952. Note how the main entrance opens inward onto a courtyard, rather than facing the street. Cram & Ferguson’s portfolio included extensive work at Wellesley, Swarthmore and Princeton, as well as the landmark 1946 John Hancock tower in Boston’s Back Bay.

As you near Morehead Street, pause at Covenant’s small circular plaza. There are seats, if you’d like to rest for a bit. Look across the street to see the Charlotte Women’s Club Building.

COVENANT POINT – Dilworth Road at E. Morehead Street

CHARLOTTE WOMEN’S CLUB – 1001 E. Morehead Street

Women’s clubs led civic activism in early 20th century urban America. The Charlotte Women’s Club pushed the city to build parks, adopt a building code that required indoor plumbing, and institute a planning department. Their love of good building shows in their 1924 clubhouse. Architect C.C. Hook, who also did the Charlotte City Hall on East Trade Street, the U.S. Courthouse on West Trade Street and the James B. Duke Mansion in Myers Park at about this same time, provided the serenely elegant NeoClassical design.

The Charlotte Women’s Club building is an official Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Landmark.

There is no crosswalk on Dilworth Road, so cross carefully in mid-block. Walk down Dilworth Road to East Morehead Street.

Turn left on East Morehead one block to Myrtle Avenue.

As you walk, admire the Addison Apartments high-rise to your right across Morehead Street.

ADDISON APARTMENTS – 831 E. Morehead Street

Apartment hotels were all the fashion in big cities such as New York during the 1920s. Maybe local construction magnate J. A. (for Addison) Jones spent time in NYC? Jones hired Charlotte architect Willard G. Rogers (whose house we will see at 524 East Boulevard) to design the tower in 1926. Today it is an office building.

Addison Apartments is an official Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Landmark and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

DUKE ENDOWMENT – 800 E. Morehead Street

James B. Duke, cigarette industrialist from Durham, N.C., used part of his fortune to start what is now Duke Energy, one of the pioneering electric utilities in the United States – and made a second fortune. In 1924, in the sunroom of his mansion in Myers Park, he signed papers to create the Duke Endowment. Today worth nearly $4 billion, the Endowment continues to assist Duke University, Johnson C. Smith University, Davidson College and Furman University, as well as healthcare and Methodist causes. San Francisco-based architecture firm Gensler designed this understated headquarters in 2014.

MYRTLE APARTMENTS – 1121 Myrtle Avenue

To fight the economic stagnation of the Great Depression, President Franklin Roosevelt created the Federal Housing Administration. The FHA helped banks make long-term, low-interest loans – which led to Charlotte’s first big “garden apartment” complex. Myrtle Apartments, 1937, features elegantly simple Art Moderne buildings around a landscaped courtyard. Look for round porthole windows, glass block and horizontal stonework bands – all Moderne touches.

Converted to condominiums in 1983, the Myrtle Apartments is an official Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Landmark.

Continue up Myrtle Avenue for three blocks. Just over the crest of the hill, you’ll see Latta Park ahead of you and on your left.

Edward Dilworth Latta initially built Latta Park as an entertainment destination at the end of his streetcar line. A dance pavilion, a boating pond and a ferris wheel encourged folks to ride out on weekends – spending nickles on Latta’s streetcars and taking a look at his houselots.

The 1911 Olmsted plan laid out streets on part of the orginal parkland and re-envisioned the rest as a quiet, natural oasis.

The Olmsted firm, known for naturalistic landscape design, had begun with Fredrick Law Olmsted’s planning of Central Park in NYC in the 1860s. By 1911 his sons Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and John Charles Olmsted were in charge. Their projects in the early 1910s included major parks in Atlanta, Baltimore, Denver, Seattle and Spokane.

At this point you have a choice of two routes:

NATURE SHORTCUT ROUTE (12 minutes). Walk through Latta Park back to the yellow sculpture. To start: turn left and walk down into the park. Head for the children’s playground in the heart of the park. Behind the green slide, pick up the concrete sidewalk along the creek, back to where our tour began.

NEIGHBORHOOD EXPLORER ROUTE (24 minutes). Visit the older, straight-street section of Dilworth. To start: Instead of walking into Latta Park, stay on Myrtle Avenue, take a short right on Park Avenue, then left on Lyndhurst Avenue. Walk along Lyndhurst two blocks, crossing Kingston Avenue.

CITY HOUSE -- 500 East Kingston Avenue at Lyndhurst Avenue

When this duplex went up about 1909 it was a novelty in Charlotte. Upscale attached dwellings were common in big cities up North, but rare here. Well-travelled local architect C.C. Hook called them “city houses,” predicting they would prove “popular with the Northern people who are locating in Charlotte.” The elaborate bracketed cornice recalls the Italianate style, a variant of Victorian architecture that had its heyday around the 1870s.

Official Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Landmark.

Continue walking along Lyndhurst Avenue one more block to East Boulevard. Turn left on East Boulevard – but first, cross the street, so that you are on East Boulevard’s right sidewalk.

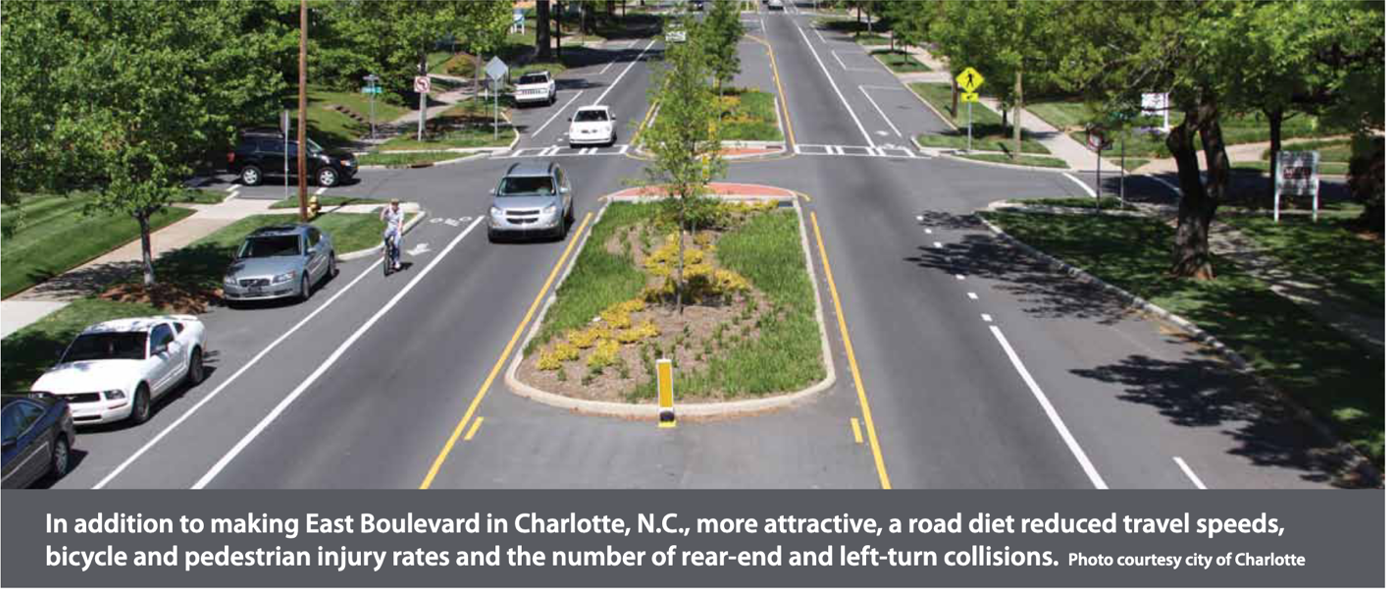

EAST BOULEVARD’S “ROAD DIET”

Edward Dilworth Latta built East Boulevard wide, with a streetcar track in the middle and ample room for horsedrawn carriage traffic on each side. But with the streetcar long-gone, motorists were treating the wide avenue as a racetrack, hitting speeds up to 60 mph. So in 2010 Charlotte’s Department of Transportation added a landscaped median and bicycle lanes – a national model for “traffic calming.”

Continue walking along the right sidewalk of East Boulevard. The Garrett House is on your left; the Rogers House will be on your right.

FRANK AND ESTELLE GARRETT HOUSE -- 501 East Boulevard, 1908

The barn-shaped roof marks this as example of Dutch Colonial design. Frank Garrett was part of Charlotte’s financial scene, vice president of a bookkeeping company called Southern Audit.

WILLARD AND EVA ROGERS HOUSE – 524 East Boulevard

Another Dutch Colonial roof graces this 1902 house built by architect Willard G. Rogers as his own residence. Wife Eva Troy Rogers served three stints as president of the Charlotte Women’s Club. During Dilworth’s decline after WWII, this dwelling and others along East Boulevard became rooming houses. In 1984 Dr. Dan Morrill and Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission purchased the Rogers House and resold it with deed covenants requiring its renovation. Higgins & Owens, a public-interest law firm, became owners in 2016.

The W.G. Rogers House is an official Charlotte Mecklenburg Historic Landmark.

KADAMPA BUDDHIST CENTER – 528 East Boulevard

When Kadampa Meditation Center moved here in 2018, it made this block one of Charlotte’s most diverse groupings of religious structures.

The building opened in 1966 as headquarters of the Greek Orthodox diocese covering much of the South. It held both offices and the residence of the Bishop.

The heavy concrete arches of the front portico reflect Brutalism, a popular architectural style in that period.

DILWORTH METHODIST – 605 East Boulevard

HOLY TRINITY GREEK ORTHODOX CATHEDRAL – 600 East Boulevard

In a city with few immigrants until recently, Charlotte’s Greek community has long stood out. Their annual September festival of food and culture, Yiasou, attracts thousands of Charlotteans. The proud cathedral rose in 1954 on the site of Edward Dilworth Latta’s own mansion. Look close and you may detect a slightly darker brick on the wings and colonnaded walkway; these were deftly added in 2017 by Charlotte-based architect Constantine N. Vrettos. Love the way that the small domes crescendo to the large central dome and cross!

Turn left on Springdale Avenue. Go one block, then turn right on Kingston Avenue.

QUADRAPLEX – 709 E. Kingston Avenue

These four-unit apartment structures are common in older Charlotte neighborhoods – cousins of the “triple-deckers” of Boston and the “three-flat” or “six-flat” buildings found in Chicago. Back before FHA financing spurred construction of sprawling multi-family complexes, small apartment structures such as this helped mingle renters among homeowners. Charlotte’s 2040 Future Plan, now under discussion, suggests revising our zoning to allow more dwellings like this.

KINGSTON AVENUE BUNGALOWS

At the end of Kingston Avenue, turn left on Park Road. When it ends in one block, turn right on E. Park Avenue.

PARK ROAD MEETS PARK AVENUE

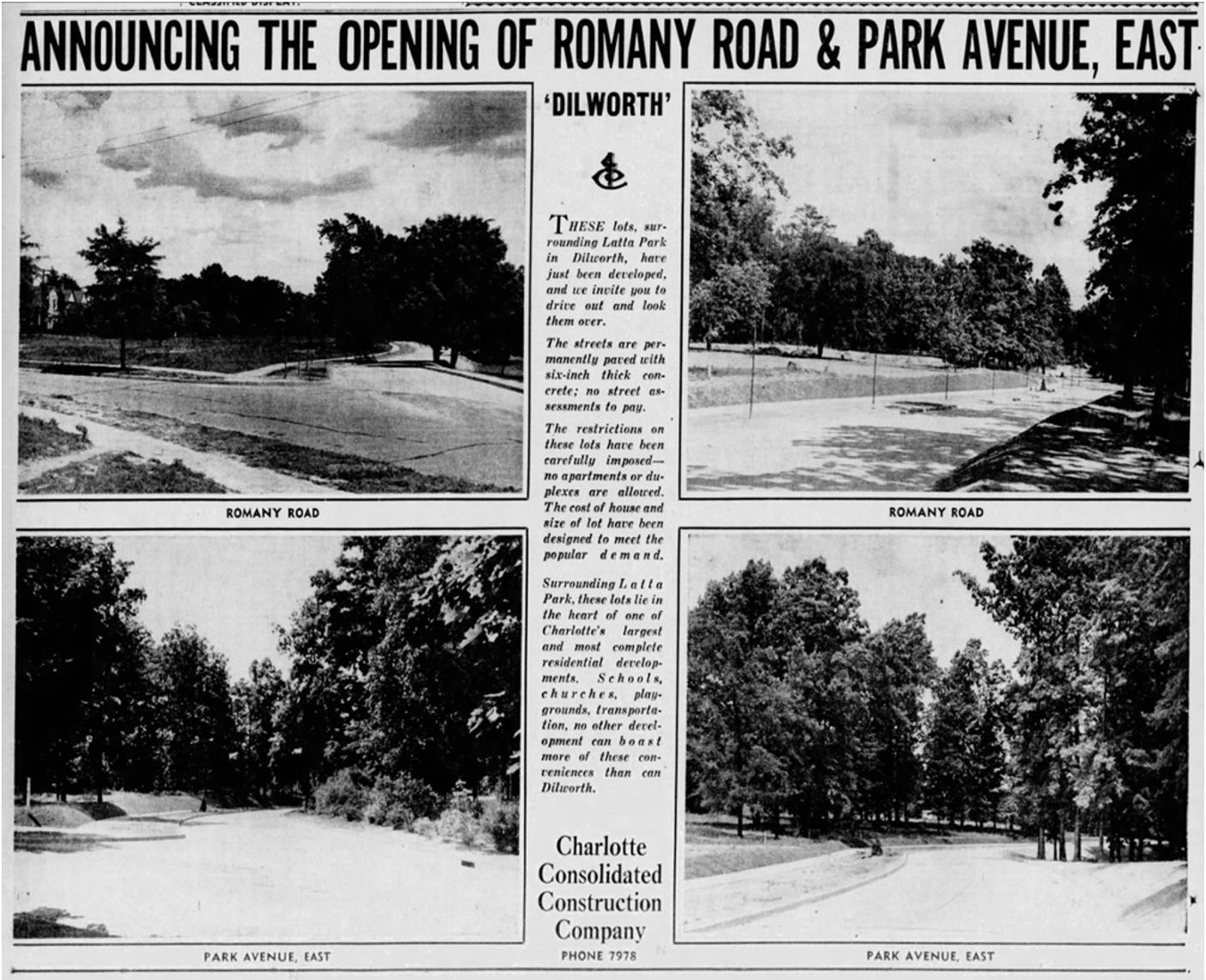

The parkside street, Park Avenue, was part of the Olmsteds’ 1911 Dilworth plan, but not built until 1939 (along with Romany Road on the other side of Latta Park). Below is a June 4, 1939, Charlotte Observer ad. I think the lower left photo was snapped where Park Avenue meets Dilworth Road. Do you agree?

Stroll down the gentle, curving slope of Park Avenue to Dilworth Road East, then turn left to the yellow sculpture.

Congratulations, you’ve completed the walk!

Want to learn more?

Check out the active Dilworth Community Association.

Tom Bradbury’s book Dilworth: The First 100 Years is at Charlotte Mecklenburg Library and is often for sale at Paper Skyscraper, 330 East Boulevard.

Dilworth is an official Charlotte Historic District and is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Essays by two local historians trace development of the 1891 section of Dilworth and the 1911 Olmsted streets.

Our Charlotte Walking Tours

Some other tours we like

Mid-Century Modern in Center City

ArtWalks Charlotte – self guided walking tours of murals and other public art

Sorting Out the New South City explores how Charlotte became a city of neighborhoods. Book discussion guide available here >>

Historic Plaza Midwood

Historic Plaza Midwood