SALAD-BOWL SUBURBS:

A history of Charlotte’s East Side and South Boulevard immigrant corridors

By Tom Hanchett

A surprising new residential pattern seems to be taking shape in American cities. Historically, dating back to the nineteenth century, newly arrived immigrants clustered in tight-packed inner-city neighborhoods, often denoted as Little Italy, Chinatown, or the like. Today, in contrast, foreign arrivals are heading outward, scattering into post-World War II suburbs. Settlement geography seems to be dispersed and multi-ethnic, usually mingling the fresh arrivals among long-time residents.

What could be called “salad-bowl suburbs” have been most remarked upon in Chicago, New York, Los Angeles and Atlanta. The Chicago Tribune, for instance, reported in 2005:

For the first time, more Latinos live in Chicago’s suburbs than in the city . . . . Latinos now make up a fifth of the six-county region . . . . Latino-owned businesses have helped revitalize broken business strips in towns such as Waukegan, Cicero and Melrose Park. And Latino homeowners account for nearly half of a recent surge of 89,000 suburban houses sales since 2000.1

The trend also appears in smaller metropolitan areas, even Pennsylvania’s depressed Allentown where Latino suburbanites quadrupled between 1980 and 2000. 2 All ethnic groups seem to be taking part, as demographer William Frey noted in his pioneering essay, “Asians in the Suburbs.”3 Intermingling of groups is evident in the suburbs of New York and Los Angeles, according to a 2000 study led by David Halle.4 Likewise in Dallas, writes reporter Pala Lavigne, old parts of the city have identifiable Latino “barrios,” but in the suburbs “roots are spread more evenly among Mexico, India, China and other places abroad.”5 Evidence of this polyglot pattern is coming from census data and also from observers on the ground.6 It is especially visible in business areas where roadside signs shout in a multitude of languages, such as in suburban Phoenix as observed by Alex Oberle, or along Atlanta’s busy Buford Highway, as chronicled by Susan Walcott.7

“Salad-bowl suburbs” is a good name for this new phenomenon. A handful of specialists in geography and demography have proposed other labels — ethnoburbia, heterolocalism, melting pot suburbs — but no name has yet stuck, perhaps because none captures the multiplicity of old and new cultures coexisting side by side.8 The metaphor of the “salad-bowl” was coined in 1959 by historian Carl Degler who sought a better image of cultural change than the older “melting pot.”9 Most scholars now agree with Degler that immigrants’ cultural distinctiveness seldom melted completely away, but rather contributed flavorful fresh components to American society. The residential intermingling now happening in suburbia takes the salad-bowl metaphor to a new level.

Salad-bowl suburbs are very evident in Charlotte. The 1990s and 2000s saw Charlotte rapidly develop two immigrant areas – the East Side (along Central Avenue, North Tryon Street, and adjacent streets), and South Boulevard. Both are very suburban in aspect, characterized by ranch houses, garden apartment complexes and small strip shopping centers built mostly during the 1950s – 1970s. Newcomers of every background live and shop here, including Latinos, Asians, Middle Easterners, Africans and eastern Europeans. While immigrants are highly visible, native-born whites and blacks still remain the majority of the population.

This chapter traces the history that produced Charlotte’s East Side and South Boulevard corridors. Both areas got started in the mid-twentieth century as workers who had gained a little prosperity in the city’s textile mills and other factories moved outward into modest new suburban housing. These white families were joined by African Americans as Civil Rights Movement victories took hold in the 1970s, a process that resulted in some all-black areas, but more mixed-race neighborhoods. History produced an array of affordable housing opportunities by the 1990s. And that was precisely what immigrants needed when they began arriving in that decade.

A family story, to begin

Roy and Polly Grant are the sweetest couple, old fashioned salt-of-the-earth white Southerners who will not let a stranger visit without taking away a jar of homemade peach preserves. I first sat with them in the 1980s in the parlor of their modest brick two-bedroom home on The Plaza in Charlotte’s Eastside, gathering tales about Roy’s life working in Carolina cotton mills and playing stringband music. Recently I asked them to recall the places they’ve lived over the years, and their story offers a useful starting point for understanding the evolution of the Eastside and also South Boulevard.Born on a Carolina farm in 1916, Roy Grant took part in the farm-to-factory migration that redefined the South in the early 20th century. He moved to the milltown of Gastonia in 1935 to find a job in the massive Firestone textile mill. There he lived “on the mill hill,” in the company housing that most Southern mills provided for their workers.

When Grant’s musical career, playing on the radio for millhand audiences, brought him to Charlotte, he and Polly again chose a factory neighborhood. Settling near friends, they lived in humble housing just outside the Highland Park #3 mill village. This working-class district known as North Charlotte (now called NoDa) huddled off North Tryon Street immediately northeast of downtown.

In the 1950s Roy took a job with the Post Office. The steady income allowed the family to qualify for a mortgage and buy their own home. Roy and Polly purchased a small, new two-bedroom brick ranch house on The Plaza. It was part of a just-created suburban area between Central Avenue and North Tryon Street, now the Eastside.

The couple raised three children and grew old together happily in their piece of the American Dream. Then in the late 1990s they made another move, to the Wilora Lake retirement facility a couple of miles away. Dealing with the vicissitudes of age was the main reason for the move.

But the fact that the community was changing also played a role. No longer was the neighborhood a place of familiar, old-fashioned Southerners. Today a Spanish speaking family lives in Roy and Polly’s old home. Cambodian and Mexican stores fill the small shopping center nearby.

“Zone of Emergence:” Millhands as immigrants

Roy Grant’s move from Carolina farm to cotton mill as a young man was very typical of the Southern labor-force in general. Foreign immigrants were a rarity here, a marked contrast to the urban north. In big northern cities, huge steel mills, stockyards and massive factories drew families off farms as far away as Italy, Hungary, and Russia. The smaller cotton mills of the Carolinas, however, were able to fill jobs with people from the farms of the American South. Charlotte, like most New South cities, attracted virtually no immigrants in the early 20th century. The low-wage workers who left the farms to labor in the region’s textile mills came from the hills and hollers of the American South itself.

It is interesting to explore parallels between millhands in the South and immigrants in the North in terms of housing patterns. When poor white Southern farm folk arrived in the city, they were as segregated as any ethnic group in the metropolitan North. A downtown Charlotte minister wrote in 1903:

Just at this period in the development of mill people it seems to be better to allow them to … form a class to themselves…. If this tendency to become a separate class is not resisted, and churches and schools are provided to these people, all to themselves, they … do better than where mill people and others are mixed promiscuously.10

Mill families were housed in carefully delimited company-owned villages set apart from the middle-class city – and also set apart from the city’s African American neighborhoods. The North Charlotte industrial area, planned in 1903 around the Highland Park # 3 cotton mill, was the largest of these blue-collar neighborhoods-of-arrival.

In northern cities, immigrant families who prospered and began to move up in the world often physically moved outward to a “Zone of Emergence.” 11 First described by Robert Woods and Albert Kennedy in Boston in 1914, such a place included modest new suburban single-family cottages intermingled with small rental apartment dwellings (triple-deckers in the Boston example). Such areas offered less crowding, more green space, and better prospects for homeownership that the initial tenement districts. But they were decidedly less grand than the fine suburbs of the wealthy business-owning classes.

Geographers have offered various models of where the Zones of Emergence tend to locate in the city.12 In the 1920s Chicago scholars Robert Park and Ernest Burgess sketched a now-classic diagram showing a ring of “workingmen’s” neighborhoods just outside the center city. In 1939, sociologist Homer Hoyt observed that residential zones often took the forms of wedge-shaped sectors, dividing the city like slices of a pie.

In Charlotte, the two pie-shaped wedges of neighborhoods on the East Side and along South Boulevard functioned as the city’s Zones of Emergence. Former millhands and others on the cusp between blue-collar and white collar economic levels moved outward into freshly constructed suburbs after World War II. Like in immigrant Boston, these areas mingled modest single-family dwellings with rental apartments – a budget version of the grander suburbs on Charlotte’s southeast side.

Creating the East Side and South Boulevard corridors

Suburbia has a somewhat different meaning in Charlotte than it does in most non-Southern cities. State laws throughout much of the South make it easier for cities to annex outlying territory. In places such as Chicago and New York, suburbs became separate incorporated municipalities. Here, however, they were brought into the city soon after they were built. In governmental terms, this means that much of the urban-suburban battling that hurt metropolitan unity in the North was not evident here. But in terms of the built environment Charlotte’s suburbs looks pretty much like those elsewhere in the United States. The car is king, sidewalks are rare, and strip shopping plazas line the main streets.

Charlotte grew rapidly in the years after World War II. As late as the mid 1940s, the city boundary ran barely two miles from downtown. It crossed Central Avenue a few blocks past The Plaza, bisected North Tryon Street at 36th Street and hit South Boulevard at Remount Road. That compact city mushroomed over the next twenty-five years. By 1970 the boundary rested some four miles from downtown. Charlotte’s land-area tripled in these decades from barely twenty square miles to over sixty-five square miles.13

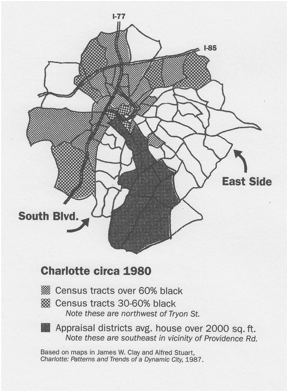

As in many U.S. cities, that growth was sectoral in character, resulting in a city of pie-shaped wedges closely identified by income and race. African Americans initially suburbanized to Charlotte’s northwest, a pattern triggered partly by the nineteenth century campus of Johnson C. Smith University, an historically black college. By the mid twentieth century, if you drove out Beatties Ford Road, the major radial street running outward from the center city, you would see mostly black faces. Well-to-do whites settled southeast, drawn to new suburbs beyond the posh 1910s-20s garden suburbs of Myers Park and Eastover. If you traveled out Providence Road, the main southeast radial, upper income white suburbia was what you would see.

For less elite whites, the east and the south became the favored sectors. On Charlotte’s east side, Central Avenue, The Plaza, and North Tryon Street extended northeastward from the vicinity of the mills that clustered at North Charlotte. Similarly on the south side, South Boulevard ran southward from the mills at Dilworth, paralleling the industrial zone along the Southern Railroad. Suburban Charlotte looked like a pie with wealthy whites living in the southeast slice, blacks residing north and west, and these less well-to-do whites with working class backgrounds located in two slices that extended south and east-northeast.

For less elite whites, the east and the south became the favored sectors. On Charlotte’s east side, Central Avenue, The Plaza, and North Tryon Street extended northeastward from the vicinity of the mills that clustered at North Charlotte. Similarly on the south side, South Boulevard ran southward from the mills at Dilworth, paralleling the industrial zone along the Southern Railroad. Suburban Charlotte looked like a pie with wealthy whites living in the southeast slice, blacks residing north and west, and these less well-to-do whites with working class backgrounds located in two slices that extended south and east-northeast.

The sectors of lower-end white neighborhoods were nice places. Small one-story “ranch” houses appeared first, most around 1000 square feet. Rental units were also commonplace, including duplexes that looked like slightly larger ranch houses, and the occasional project that might contain half a dozen apartments. Over time, bigger and bigger dwellings appeared. The upward economic progress of the initial families, plus Charlotte’s general growth which attracted middle-income arrivals from all over the country, pushed newly constructed Eastside and South Boulevard houses into the 2000 square foot range by the 1970s. Charlotte’s truly wealthy still gravitated southeast, but for all other economic levels, the Eastside and suburban streets off South Boulevard were highly desirable places.

Businesses followed the general suburban trend of the 1950s – 1970s. Small-scale strip shopping popped up along the transportation arteries, usually groups of two or three stores facing a parking lot. In 1968 an enclosed shopping mall anchored by a Woolco discount store went up on North Tryon, but soon foundered economically. In the mid 1970s the Eastside unexpectedly gained a grand regional mall. Eastland Mall boasted three major department store anchors, two levels of specialty stores, plus an ice skating rink and Charlotte first multi-restaurant “food court.” Some observers wonder how it could compete with just-opened Southpark mall in Charlotte’s rich southeast sector. But to most people, Eastland Mall seemed a solid signal that this once humble side of town had really arrived.

And the Eastside and South Boulevard areas were also attracting major multifamily housing investment. During the 1970s and early 1980s, a nationwide trend in construction of “apartment communities” played itself out along arteries in these areas. Clusters of two and three story buildings set in attractive landscaping, often with swimming pools, fountains and clubhouses, were marketed to young professionals. Developers of both the strip shopping and apartment complexes found it relatively easy to build on the Eastside and in the vicinity of South Boulevard. Posh southeast Charlotte had less such construction, because politically well-connected citizens could block development, and the majority-black west and northwest had even less, owing to investor perceptions of marketability.

As the 1990s dawned, the Eastside and South Boulevard sectors possessed some of Charlotte’s highest suburban residential densities and plenty of small retail space close to housing. Storefronts sometimes went vacant, losing out to big-box competition, and the smaller houses and 1950s duplexes sometimes struggled to find tenants, reflecting the rising aspirations of Charlotte residents. Yet even with the arrival of upwardly mobile African Americans since the 1970s, the Eastside and South Boulevard sectors of Charlotte remained solidly middle-class and desirable, exactly the sort of “Leave It to Beaver” / “Brady Bunch” suburbia celebrated on TV sit-coms.

From all-white to racially mixed

The racial integration of Charlotte’s suburbs is worth examining in some detail. The American South is, of course, known for sharp racial separation in the early twentieth century and for staunch defense of segregation during the Civil Rights Era of the 1950s and 1960s. But scholars have begun to note an impressive turn-about in racial patterns since the 1970s.

Beginning with the Fair Housing Act of 1968, “equal housing opportunity” became a watchword of lenders and real estate sellers nationwide. “Data from Census 2000 show that black-white segregation declined modestly at the national level after 1980,” concludes an article in the journal Demography. And for reasons not fully understood, “declines were centered in the South and West.”14 In Charlotte, civic leaders made a point of welcoming integration, especially after the local schools became the national test case for court-ordered busing: Swann v Charlotte-Mecklenburg, 1971. In 1970 Charlotte ranked as the United States’ fifth most segregated city.15 By 2000 the city had become the nation’s second least segregated urban place.16

The Eastside and South Boulevard corridors, comfortably middle-class but not overly expensive, became desirable places for suburbanizing African Americans. This brought some tensions. Hidden Valley, a middle-income subdivision off North Tryon Street, tried to hold on to white residents but became all black, as did several other pockets on the Eastside. But more often, whites and blacks found ways to co-exist.

A look at U.S. Census data for the six census tracts along the Central Avenue corridor, for instance, shows this transition. In 1960 the entire area was overwhelmingly segregated, every tract nearly 100% white. In the mid-1960s, the Belmont-Villa Heights neighborhood switched abruptly from all-white to all-black, apparently because of overt actions of landlords who funneled in African Americans displaced by Urban Renewal clearance elsewhere. After 1968, however, that kind of racial steering would no longer be legal. The Plaza-Midwood neighborhood, adjacent to Belmont-Villa Heights, became 77% white / 21% black by 1980. That was very close to the city-wide ratio of 79%/20%.17 It has held that mixture through 2000. Other tracts showed a similar pattern. Except for Belmont-Villa Heights, all neighborhoods along Central Avenue were between 71% and 86% white by 1990.

So it seems that Fair Housing regulations worked – not perfectly, to be sure, but well enough to bring substantial racial integration. Racially mixed neighborhoods came into existence, with a fair amount of stability over time , rather than abrupt white flight. Southern whites – contrary to the fearful rhetoric of Civil Rights opponents – could accept neighbors who looked different from themselves.

Foreign immigrants arrive

Jose Hernadez-Paris still vividly remembers when he saw the first Mexican restaurant actually run by Mexicans in Charlotte. Jose’s parents had emigrated from Columbia, South America, in the 1970s, rare foreigners in this overwhelmingly native-born town. Driving down South Boulevard one day in the 1980s, the family saw a sign for a restaurant called El Cancun about to open in a disused fast-food franchise. Mexicans were at work renovating the interior. The Hernandez-Paris family were so excited they stopped the car and pitched in.

A few years later, Latino construction crews arrived to set the steel for the towering Bank of America (then Nationsbank) skyscraper, completed in 1992, that still defines the uptown skyline. English-Spanish speakers were still hard to find, and Hernadez-Paris was called upon to help translate construction documents. But things were about to change. Geographer Owen Furuseth suggests that the skyscraper crews returned to their homelands with news of a clean, economically thriving Southern city where jobs seemed plentiful.18 Whatever the exact mechanism, Latino movement to Charlotte quickly swung into high gear.

During the decade of the 1990s, this city which had experienced virtually no foreign immigration during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries suddenly emerged as a magnet for newcomers from around the globe. A hot economy led by banking – Charlotte became the nation’s second-largest banking center circa 2000, second only to New York City – meant that there were plenty of jobs, including entry-level service positions. A Brookings Institution survey marked Charlotte as the fourth-fastest growing Latino city in the United States during the 1990s, and a subsequent Brookings study named it the nation’s second-fastest during 2000 – 2005. Mexicans were the largest single immigrant group, but Hispanic arrivals came from every Central American and South American nation. Charlotte’s second-largest country of origin was Vietnam, seeded in part by resettlement of Vietnam War refugees in the city by Catholic Social Services during the 1970s. Appreciable numbers of Asians also immigrated from Laos, Cambodia, Korea, and India. And still others newcomers arrived from eastern Europe, from Africa, from the Middle East and elsewhere.

Suburbia, not inner-city tenements

Back during America’s massive immigrant influx of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, new arrivals had flocked to tenement districts near downtowns in America’s biggest cities. Classic examples included South Philadelphia or New York City’s Lower East Side. Old, high-density multi-story buildings, largely abandoned by the suburbanizing middle class, offered few amenities – tight living quarters, rudimentary plumbing, steep stairs to climb, no green space. But rent was cheap, and the very closeness of everything made it easy to walk to many different jobs, or find customers or laborers when starting a business. Here immigrants could begin to forge a new life in America. In city and after city, people began to speak of Little Italy or Chinatown or dozens of other ethnically identified low-income districts. Once these immigrants got their feet under themselves, they would move out to the suburbs, often leaving the inner city to be occupied by the next immigrant wave.

Charlotte, in contrast, had no tenements. Back in the nineteenth century, when tenement neighborhoods were created in big urban centers of the northern U.S., Charlotte had been little more than a village, a place of fewer than 20,000 people in 1900. What few old center-city buildings it did possess were largely demolished during the rapid growth of the late twentieth century.

So instead of heading to the inner city, Charlotte’s 1990s immigrants seeking inexpensive housing found what they required in the older post-World War II suburbs. Sometimes the arrivals moved into black working-class districts, located on the north and northwest or in pockets elsewhere in the city such as Grier Heights (an African American suburb where numbers of Latinos settled), or Belmont-Villa Heights (where the city’s Cambodians initially found rental quarters). A small number of foreigners who arrived with money scattered into middle-and-upper income areas throughout the city. But most of Charlotte’s immigrants gravitated to the Eastside and South Boulevard.19

Today banners in Spanish advertise vacancies in the apartment communities. A look at people relaxing on the porches on a warm Sunday evening shows Africans, Arabs and southeast Asians as well. Because of the density of apartments and small houses, public transportation functions well here. On Central Avenue, the city’s busiest mass transit route, buses run every ten minutes, an important amenity that attracts even more immigrants.

The once-bedraggled small strip shopping centers, easily walkable from the apartment complexes, have flowered into vibrant miniature “downtowns.” Most cater to not one but several ethnic groups. Latino “tiendas” (grocery stores) and Asian markets offer a mix of basic American and imported goods. As populations grow, restaurants and specialty stores are popping up. On one corner on Central Avenue, a Bosnian grocery shares a parking lot with a Vietnamese pool hall, within sight of an African coffeeshop and a Mexican taqueria. Three stoplights further on, another cluster contains a Latino store specializing in Christian books and gifts, the Carneceria Mexicana butcher shop and grocery, a Vietnamese wholesaler servicing the city’s nail-care salons, and the Jerusalem Barber Shop whose customers are mostly Middle Easterners visiting the nearby Muslim mosque. Even “American” businesses have an international flavor, such as Central Avenue’s Walmart crowded with customers speaking a dozen languages, or a Starbucks not far away where Somali cab drivers sit in a circle under a tree, continuing an old African custom of coffee conversation.

The bustling entrepreneurial scene is beginning to stimulate new construction. In the 1990s, a Vietnamese family ambitiously converted the abandoned Woolco shopping center on North Tryon Street into Asian Corner Mall with new red-roofed “pagoda” towers. Today the mall is still struggling for solvency, but smaller projects are finding success. In half a dozen spots, developers have demolished older buildings and put up compact groups of stores intended to attract immigrant businesses. Go into those stores, and near the cash register you’ll find cards for other start-up entrepreneurs – painters, contractors, auto mechanics, and many real estate brokers.

Indeed, outsiders can get the erroneous impression that the Eastside and South Boulevard are all-immigrant. Remember the six census tracts adjoining Central Avenue, noted for their 1990 racial integration earlier in this essay? In 2000 native-born whites remained the largest group in all those areas, followed by native-born blacks. Looking at the city as a whole, geographers Owen Furuseth and Heather Smith found only a single census tract in 2000 had a Latino majority.20

Indeed, outsiders can get the erroneous impression that the Eastside and South Boulevard are all-immigrant. Remember the six census tracts adjoining Central Avenue, noted for their 1990 racial integration earlier in this essay? In 2000 native-born whites remained the largest group in all those areas, followed by native-born blacks. Looking at the city as a whole, geographers Owen Furuseth and Heather Smith found only a single census tract in 2000 had a Latino majority.20

Will Charlotte’s salad-bowl suburbs persist? Or is this just a temporary illusion of integration? It is possible that whites, and native born blacks as well, will depart over time. Both the Eastside and South Boulevard are currently struggling to get adequate school resources, to deal with perceptions of crime, and with other challenges. Patterns will be clearer once counts are in for the 2010 Census and those beyond.

A New South

Charlotte’s new urban geography marks the years around 2000 as the emergence of yet another “New South.” The term dates to the post-Civil War period when Southern leaders sought to rebuild this formerly agricultural region as a place of cities and factories. Re-invention has continued apace over the years, and scholars now point to several successive New Souths.21 The current era of change may be the most remarkable. Just a generation ago the South was known for segregation, blacks and whites kept separate both by deep-seated cultural attitudes and by law. That racial landscape has changed dramatically, but painfully and haltingly – as the current trend toward re-segregation in the schools of Charlotte demonstrates.

If you had predicted a generation ago that the South would become a magnet for immigrants, most Southerners would have expressed disbelief. That those ethnic groups would not be segregated, but rather intermingled into all areas where affordable housing exists, would have engendered even stronger skepticism. Yet that is precisely what has happened in the South Boulevard corridor and on the East Side of Charlotte. The post-World War II suburban neighborhoods that were once Zones of Emergence for blue-collar white Southerners are now salad-bowl suburbs, places of both arrival and upward mobility for newcomers and long-time residents of the New South.

1 Antonio Olivo and Oscar Avila, “Latinos Choosing Suburbs Over City,” Chicago Tribune, November 1, 2005.

Others on Chicago: Louis DeSipio, Counting on the Latino Vote: Latinos as a New Electorate (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1996). Sapna Gupta, “Immigrants in the Chicago Suburbs,” policy paper prepared for Chicago Metropolis 2020 (February 2004). David A. Badillo, “Mexicans and Suburban Parrish Communities: Religion, Space and Identity in Contemporary Chicago,” Journal of Urban History 31:1 (November 2004), 23 – 46. Richard P. Greene, “Chicago’s New Immigrants, Indigenous Poor, and Edge Cities,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 551:1 (1997), 178 – 190.

2 Lillian Escobar-Haskins and George F. Haskins, “Latinos in the Lehigh Valley: The Dynamics and Impact of this Growing and Changing Population,” (Lehigh Valley, PA: Lehigh Valley Economic Development Corporation, 2005).

3 William P. O’Hare, William H. Frey, Dan Frost, “Asians in the Suburbs,” American Demographics 16:5 (1994), pp. 32 – 38. Also Richard D. Alba, John R. Logan and Shu-yin Leung, “Asian Immigrants in American Suburbs: An Analysis of the Greater New York Metropolitan area” in Mark Baldassare, ed.,Suburban Communities: Change and Policy Responses. Research in Community Sociology, Volume 4. (Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 1994), pp. 43 – 70.

4 David Halle, Robert Gedeon and Andrew A. Beveridge, “Residential Separation and Segregation, Racial and Latino Identity, and the Racial Composition of Each City,” in David Halle, ed., New York and Los Angeles: Politics, Society and Culture: A Comparative View (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), pp. 150 – 193.

Others on Los Angeles: James P. Allen and Eugene Turner, “Spatial Pattern of Immigrant Assimilation,” Professional Geographer 48 (2), pp. 140 – 155. William V. Clark and Shila Patel, “Residential Choices of the Newly Arrived Foreign Born: Spatial Patterns and the Implications for Assimilation,” (University of California – Los Angeles: California Center for Population Research, On-Line Working Paper Series, February 2004).

Others on New York: Richard Alba, Nancy Denton, Shu-Yin Leung and John R. Logan, “Neighborhood Change under Conditions of Mass Immigration: The New York City Region, 1970 – 1990,” International Migration Review 29, pp. 625 – 656. Also Richard Alba, John R. Logan and Brian Stults, “The Changing Neighborhood Contexts of the Immigrant Metropolis,” Social Forces 29 (2), 2000, pp. 587 – 621.

Scholars agree there is ethnic intermingling in suburbia but debate its extent. Allen and Turner, for instance, assert that recent immigrants still cluster somewhat more than native-born residents. See also David Fasenfest, Jason Booza and Kurt Metzger, “Living Together: A New Look at Racial and Ethnic Integration in Metropolitan Neighborhoods, 1990 – 2000,” in Alan Berube, Bruce Katz, and Robert Lang, eds, Redefining Urban and Suburban America, Evidence from Census 2000, vol 3 (Washington: Brookings Institution, 2005), 93 – ___. For an overview of the debate, read Clark and Patel.

5 Pala Lavigne, “Opportunity Knocks In ‘El Norte’: Region Attracts Immigrants from All Over, and Their Ways of Life are as Diverse as They Are,” Dallas Morning News, October 25, 2005.

6 Perhaps the first writer to note the trend was reporter Alex Marshall who observed intermingling of white, black and Filipino families in post-1970s suburban areas of Virginia Beach, Virginia: “The Quiet Integration of Suburbia,” Virginian-Pilot, July 25, 1993. More recently, April Austin, “New School, New Town, New County — Immigrant Parents and Suburban Schools: Not Always an Easy Fit,” Christian Science Monitor, January 13, 2004.

An early scholarly analysis came from sociologists Richard D. Alba, John R. Logan, Brian J. Stultz, Gilbert Marzan, and Wenquan Zhang, “Immigrant Groups in the Suburbs: A Reexamination of Suburbanization and Spatial Assimilation,” American Sociological Review 64 (1999), pp. 446 – 460. Other scholarly works include William H. Frey, “Melting Pot Suburbs: A Study of Suburban Diversity,” in Bruce Katz and Robert Lang, eds., Redefining Urban and Suburban America: Evidence from Census 2000, vol 1 (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2003), pp. 155 – 179. Roberto Suro and A. Singer, Latino Growth in Metropolitan America: Changing Patterns, New Locations (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy, 2002). Janet Rothenberg Pack, ed., Sunbelt/Frostbelt: Public Policies and Market Forces in Suburban Development (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2005), p. 22. Jon Teaford, The Metropolitan Revolution; The Rise of Post-Urban America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006), pp. 223 – 224.

7 Alex Oberle, “Latino Business Landscapes and the Hispanic Ethnic Community,” in David H. Kaplan and Wei Li, eds, Landscapes of the Ethnic Economy(Rowman & Littlefield, 2006), pp. 149 – 163. Alex Oberle, “Se Venden Aqui: Latino Commercial Landscapes in Phoenix, Arizona,” in Daniel D. Arreola, ed.,Hispanic Spaces, Latino Places: Community and Cultural Diversity in Contemporary America (Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 2004), pp. 239 – 254. Susan M. Walcott, “Overlapping Ethnicities and Negotiated Space: Atlanta’s Buford Highway,” Journal of Cultural Geography, 20 (1), 2002, pp. 51 – 75. Kirk Kicklighter, “Rainbow Atlanta: Census Shows Racial Barriers Disappearing in City, Suburbs,” Atlanta Journal and Constitution, May 6, 2001.

8 Li Wei, “Ethnoburb Versus Chinatown: Two Types of Urban Ethnic Communities in Los Angeles,” Cybergeo. Vol 10. (1998) p. 1-12. Wilbur Zelinsky, The Enigma of Ethnicity: Another American Dilemma (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2001), pp. 124 – 154. Frey, “Melting Pot Suburbs,” in Katz and Lang, eds., Redefining Urban and Suburban America: Evidence from Census 2000.

9 Carl N. Degler, Out of Our Past: The Forces that Shaped Modern America 3rd ed. (New York: Harper Perennial, 1984), p. 332, originally published in 1959.

10 Charlotte Observer, August 2, 1903, quoted in Thomas W. Hanchett, Sorting Out the New South City: Race, Class & Urban Development in Charlotte, 1870s – 1970s (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1998), p. 89.

11 Albert Woods and Robert Kennedy, The Zone of Emergence 2nd ed. (Boston: MIT Press, 1969). More recently, Herbert Gans, The Urban Villagers: Group and Class in the Life of Italian-Americans, 2nd ed (New York: The Free Press, 1982). Douglas S. Massey, “Ethnic Segregation: A Theoretical Synthesis and Empirical Review,” Sociology and Social Research 69 (3), 1985, pp. 315 – 330. Robert Zecker, “’Where Everyone Goes to Meet Everyone Else’: The Translocal Creation of a Slovak Immigrant Community,” Journal of Social History, 38 (Winter 2004), 423–53.

12 Robert E. Park, Ernest W. Burgess and Roderick D. McKenzie, eds, The City (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1925). Homer Hoyt, The Structure and Growth of Residential Neighborhoods in American Cities (Washington, D.C.: Federal Housing Administration, 1939). Homer Hoyt, Where the Rich People and the Poor People Live: The Location of Residential Areas Occupied by the Lowest and Highest Income Families in American Cities (Washington, D.C.: Urban Land Institute, 1966). Scholars now caution that these models — reasonable approximations of urban form in the early and mid 20th century, respectively –- have very limited viability beyond that period. Hanchett, Sorting Out the New South City, pp. 6 – 10. Zelinsky, Enigma of Ethnicity. Michael P. Conzen, “Morphology of Nineteen Century Cities,” in W. Borah, J. Hardoy and Gilbert Stetler, eds., Urbanization of the Americas: The Background in Historical Perspective (Ottawa: National Museum of Man, 1980), 119 – 42. Michael P. Conzen, “Historical Geography: Changing Spatial Structure and Social Patterns of Western Cities,” Progress in Human Geography 7:1 (March 1983), pp. 88 – 107.

13 James W. Clay and Alfred W. Stuart, eds., Charlotte: Patterns and Trends of a Dynamic City (Charlotte: Urban Institute, UNC Charlotte, 1987), p. 31. Hanchett, Sorting Out the New South City, pp. 214, 234.

14 John Logan, B.J. Stults and Reynolds Farley, “Segregation of Minorities in the Metropolis: Two Decades of Change,” Demography (2004) 41:1. pp. 1 – 22.

15 Annemette Soresen, Karl E. Taeuber, and Leslie J. Hollingsworth, Indexes of Racial Segregation for 109 Cities in the United States, 1940 to 1970, with Methodological Appendix (Madison: University of Wisconsin, Institute for Research on Poverty, 1974), table 1.

16 Lois M. Quinn and John Pawasarat, “Racial Integration in Urban America: A Block Level Analysis of African American and White Housing Patterns,”. See also John Woestendeik and Ted Mellnik, “Fewer People Living in Racial Isolation, Mecklenburg More Diverse, More Integrated,“ Charlotte Observer, April 5, 2001.

17 Elise C. Richards, “Residential Segregation in Charlotte, NC: Federal Policies, Urban Renewal and the Role of the North Carolina Fund” (Terry Sanford Institute of Public Policy, Duke University, 2002), p. 29.

19 In addition to the essays in this present volume, see Heather Smith and Owen Furuseth, “Making Real the Mythical Latino Community in Charlotte, North Carolina,” in Smith and Furuseth, Latinos in the New South: Transformations of Place (England: Ashgate Publishing, 2006), pp. 191 – 216.

Generally on the cultural clashes between old and new Southerners, read David Goldfield, “Unmelting the Ethnic South: Changing Boundaries of Race and Ethnicity in the Modern South,” in Craig Pascoe, Karen Leathem and Andy Ambrose, eds., The American South in the Twentieth Century (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2005), pp. 19 – 38.

21 James C. Cobb, “From the First New South to the Second, the Southern Odyssey Through the Twentieth Century,” in Pascoe, Leathem and Ambrose,The American South in the Twentieth Century, pp. 1 – 18.