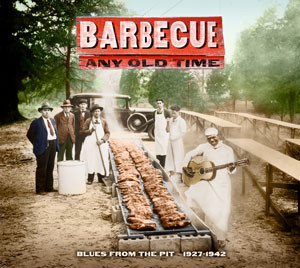

Barbecue Any Old Time

Blues From The Pit 1925-1949

“Growing up, when we ate barbecue it was on special occasions,” recalls North Carolinian Ed Mitchell, one of the nation’s most respected African-American barbecue pitmasters. “My uncles who had left the farm and gone up North, they would come back for Christmas-time. That was a time of celebration, and we would cook barbecue for them.”

“Come with me – down to the jamboree, The main attraction will send you – that good old Southern barbecue” -Nat King Cole (born 1919 in Montgomery, Alabama) Riffin’ At The Bar-B-Q (recorded 1939 in Hollywood, CA)

In this collection of vintage blues and jazz you can hear the fun of those rural frolics and feast days. Listen closely and you’ll also hear something else – a new metropolitan America where barbecue became an urban commodity, available any time you had cash in hand.

The Great Migration of the early twentieth century carried black and white Southerners from hard luck farms to the big cities of the North and West. Nearly every one of these musicians made that difficult and exciting journey, moving from a world where you were under the landowner’s thumb, to a land of plenty where you could get whatever you desired. Or at least that’s what you boasted, regardless of reality. For indeed these are boasting songs, not all that far removed from today’s hip-hop music. Barbecue was part of an urban lifestyle, a little like the flashy luxury goods that today’s rappers show off. On these old records, barbecue stands in for all that is good – money in your pocket, someone eager for your sexual charms. Oh, and lots of fine food whenever you want it.

* * *

What is barbecue? When Columbus showed up in 1492, he noticed Indians slow-cooking meat, a practice they called barbacoa. A 16th-century painting by French explorer Jacques Le Moyne shows Indians in Florida laying out their diverse game – fish, mammals, and reptiles alike – on a framework of wooden stakes erected over burning logs. George Washington, procuring meat for his troops during the French & Indian War, spoke of “barbecuing it in the Indian manner,” and barbecues became popular political campaign events in the days of the Founding Fathers. Barbecue has been a fixture at political rallies ever since, especially in the South. As Raleigh Times editor Herbert O’Keefe once reminded his readers: “No man has ever been elected governor of North Carolina without eating more barbecue than was good for him.” Pitmaster Ed Mitchell puts it this way: “Barbecuing is going to be done, you know. Even when the politicians do it, they need the voter, and that’s a way of bringing them together.”

There is no truth, by the way, to the notion that “barbecue” derives from French words meaning “beard to tail.” A journalist covering politician Andrew Jackson, noting his supporters’ love of whole-hog barbecue, made that pun, which got picked up as gospel truth. “Absurd conjecture,” writes the Oxford English Dictionary. “Flagrantly fatuous Franco-poop,” opines food writer C. Clark “Smoky” Hale. Lots of other ethnic groups contributed to barbecue, creating a uniquely American food. Scholars John Shelton Reed and Dale Volberg Reed document German heritage in North Carolina’s vinegar-and-tomato preparation. The Southern Foodways Alliance’s Barbecue Oral History Project has uncovered Greek heritage in the dry rubs favored in Memphis. Mexicans, who still call their food barbacoa, may have contributed the practice of cooking in a pit in the ground. Pepper sauces seem to have come from Africa, and it was often black men who put in the hard, long hours required to tend barbecue’s distinctive slow cooking.

“Pepper Sauce Mama, you make my meat so hot.” -Charlie Campbell, Pepper Sauce Mama (recorded 1937 in Birmingham, Alabama)

The South is the heartland of American barbecue. Elsewhere “barbecue” is a verb, “to cook something outdoors.” But in the South, “barbecue” is a noun. It’s that special meat – beef brisket in Texas, lamb in Kentucky, pork most everywhere else – prepared in your homeplace’s special tradition. Brownie McGhee sings that truth when he nods to other states’ specialties before saluting the pulled pork favored in North Carolina and East Tennessee where he grew up:

“Barbecue chicken, barbecue lamb, Barbecue beef, barbecue ham. When you fix that table for me, Make it plain barbecue just as sweet as can be.”

* * *

When Brownie McGhee recorded those lines, he was in New York City, far from his native turf. Over five million African-Americans left the South during the first half of the 20th century seeking urban opportunity beyond the Mason Dixon Line. More than twice that number of whites made the same journey. Even if they didn’t depart Dixie, farm folk moved to the booming cities of the South. Barbecue moved along with them.

“I was borned in the country, But Daddy I was raised in town.” -Georgia White (born 1903 in Sandersville, Georgia) Pigmeat Blues (recorded 1936 in Chicago)

“A lot of the barbecue sold by African-Americans was done out of their homes or using makeshift cookers on the corners of black neighborhoods – finding the capital to open a place was hard to come by,” says Georgia barbecue historian Dr. Craig Pascoe. Even so, the food proved irresistible, and it wasn’t unusual for whites to make stealthy visits to black-owned barbecue stands for a delicious take-out dinner.

“When you come to my house, Come down behind the jail, I got a sign on my door ‘Barbecue For Sale.’” -Lucille Bogan (born 1897 in Armory, Mississippi) Barbecue Bess (recorded 1935 in New York City)

As the Great Migration carried Southern barbecue to new locales, it did the same for Southern music. Jazz, born in the sporting houses of New Orleans, followed the river boats north to St. Louis and Chicago, and spread from there. Blues from the Mississippi Delta traveled Highway 61 to Memphis, then on to the Windy City, while the piedmont blues of Georgia and the Carolinas rode the rails to New York City. Jazz, blues, and barbecue would eventually sweep the nation. Barbecue restaurants began popping up in American cities during the 1910s-1920s. They emphasized a down-home vibe, but actually were temples of newness, places where the old feasting celebrations happened every day. When Frankie “Half-Pint” Jaxon sings about Jasper’s Barbecue – run by drummer Jasper Taylor in Chicago – in the same breath he mentions the new medium of radio, “Station JB broadcasting!” and the just-perfected electric jukebox, “You drop a nickel in the slot and holler ‘let her go!’”

“I was walking down the street today… And I walked right in a swell cafe” -Bogus Ben Covington, (born c.1900 in Columbus, Mississippi) I Heard The Voice Of A Pork Chop (recorded 1928 in Chicago)

It wasn’t good to look too newfangled, though. Big city eaters hungered to connect with “country,” with “tradition.” Even as Tidwell’s Barbecue attracted motorcar patrons to its suburban Atlanta location in the late 1920s, its promoters took care to showcase pitmaster Bob Hicks, a down-home blues guitarist. As “Barbecue Bob” he became the symbol of the restaurant – and a major national recording artist.

* * *

So settle in and give a listen. Barbecue Bob will guide your way. Savor the boisterous boasting, the sly winks, the snappy musicianship. We think you’ll agree, these blues are sure cooked to a turn. And if you find yourself getting hungry, well…

“We serve the neck bones, beans, beans without,

Pig’s tails, pig’s snoots and sauerkraut,

Pickles, onions, mustard, too,

Corn beef hash and kidney stew.

People listen, I want to tell to you,

What goes on at Jasper’s Barbecue…

Some order ribs, some order pork and beans,

They serve the best fried pies you ever tasted or seen.”